DIGITAL AS A SIGHT FOR CIRCUS

“We are all living with digital media and I feel like making shows without

that is kinda halfway there. We really try and make a world on stage that

reflects the world that we live in”

(The Builders Association, 2014).

At the end of march 2020, I found myself stuck in Latvia. Covid had brought the world to a standstill. How could I not let the situation influence the journey of my work? The pandemic brought to question some of the fundamentals of being human, and therefore also questioned what it means to create Circus and the spaces it inhabits. You, the reader, will most likely be reading this using some form of digital technology. I can place a link Here. My words no longer just hold the same meaning as they once did in the non-digital world but can be enhanced, manipulated, tweaked. In this space, the word Here does not just mean here at all. It also connects you to the digital there. The word now reaches further into the world than the dictionary meaning. If you would like you can click the link and listen to some lofi while reading this. You will also notice it is a live space, not just extending into content but potential live interactions. Hyperlinks subvert hierarchies (Searls and Weinberger, 2015). Our lives today are interwoven with technology, Katherine Hayles refers to this phenomenon as Technogenisis, the coevolution of humans and technics. The exponential growth of digital technology over the past thirty years has now become part of the body, altering and recreating our being in the world. We are no longer confined to libraries and text to be educated. With podcasts, YouTube channels, Twitch live streams, audiobooks, Netflix, we can access information from our digital pockets.

Technology Is Nothing New

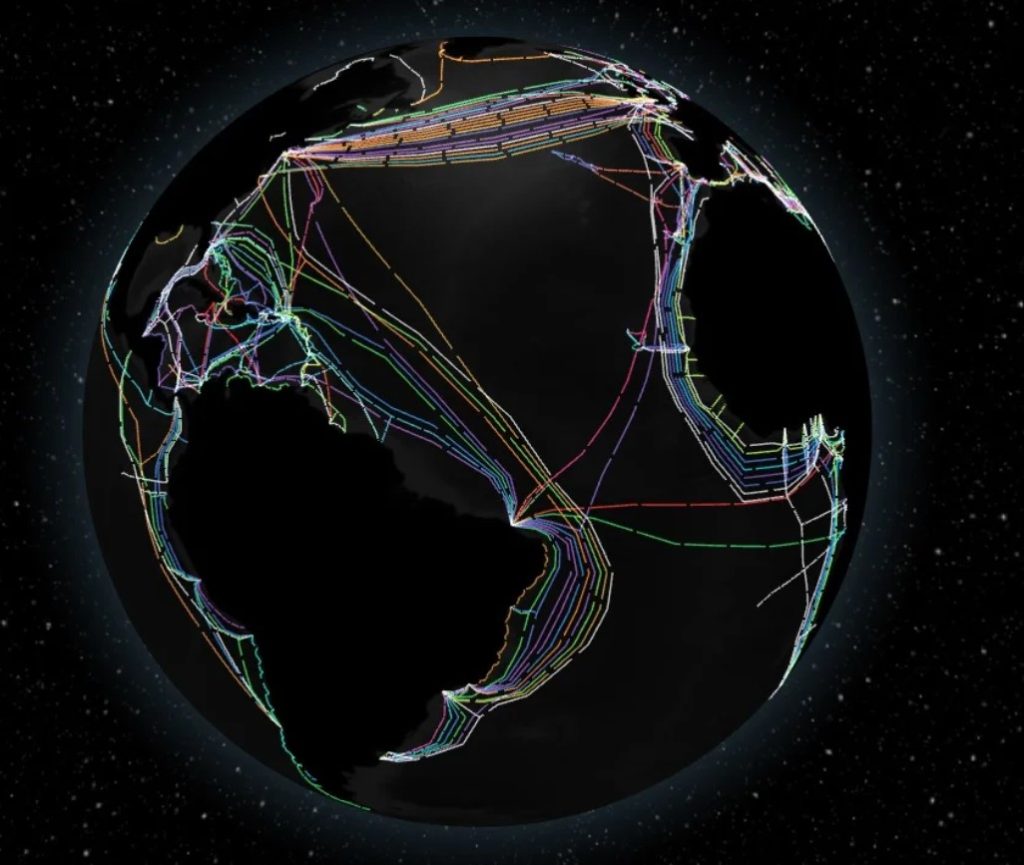

Humans are defined by their tools and now those tools are digital. “People use technology only to mean digital technology. Technology is actually everything we make” (Atwood, 2013). We have created technology since we first picked up a rock 200 million years ago. Then, at some point, came the wheel, some stuff happened in between and now we have virtual reality headsets. Both the first rock we picked up, and virtual reality are made by the same hands, and both aim to extend us further into the world. “Humans are defined by their tools, and with each technology, a completely new human environment is created” (McLuhan, 1973). “Digital technology not only augments and expands our capacities in the world but replaces and undermines them as well, in ways we are only beginning to learn” (Doc Searls). We see today that the internet has connected people and ideas from around the world, news and content can spread faster than ever before and the internet is always ready to bring you information. “We build the tools and then the tools build us” (McLuhan, 1973). Technology has been shaping our existence since that first rock. The invention of the wheel has completely reshaped humans. More efficient transportation closes the distance between communities, shaping our cities, trade, sport, and entertainment. These are just some crude examples of how the wheel has ‘made us’.

“The most profound technologies are ones that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it” (Wieser, 1991).

The blind man uses his stick to experience the world. The stick informs the blind man of his surroundings. The vibrations the stick picks up run through the body, giving real-time feedback to the blind man. The stick takes time to master, but once the user is competent, The physical object disappears from perception, becoming an extension of one of the limbs. At that moment in time, for the blind man, the stick doesn’t exist. “The blind man’s stick has ceased to be an object for him and is no longer perceived for itself” (REYNOLDS, 2017). The stick broadens the blind man’s experience. The hand-balancer and their hand-balancing canes can be compared to the blind man and his stick. Once the hand-balancer has become competent with their technology (discipline) the canes also disappear. They are no longer an object but have now become an extension of the hand-balancers subjective physical reality. Technology and humans merge. “The relation between humans and technologies is part of a larger relation, between human beings and their world, in which technologies play a mediating role” (Broadhurst and Price, 2017).

The rock, Merleau Ponty’s blind man’s stick, and the handstand canes are all examples of mechanical technology. But what happens when we speak about the digital era? Where our technologies have transcended our experience of space and time, our relationship with technology has become more complicated. If we take the smartphone as an example, the mechanical part of it becomes an extension of our actions. We say we are calling someone, not that the phone is calling someone. When we like a photo on Instagram, in our experience it is us liking the photos, not our phones. In these examples, the phone also becomes an extension of ourselves, disappearing from our perception in the acts of use. The complexities arise not in the digital technology itself, but in the ever-expanding world, it creates.

McLuhan believes that humans have used tools to extend themselves in space (mechanical technology, e.g. the rock) reaching out into the world. We have extended our body, with the use of objects, into the objective world, but what does digital technology extend us towards? Heidegger argues that the objective world is only part of the human experience, and from this phenomenological viewpoint, I propose that digital technology is extending humans not just towards the objective world, but somewhere else entirely.

Humans & The Internet. When we describe an object, we can name the attributes of the object. We can describe it by weight, shape, colour, temperature, etc. This gives us a certain view of the world through categorization. We can do the same with humans, breaking down what we are made from into smaller and smaller categories to describe who we are. Heidegger suggests that our experience of the world is as important as the data we extract. If we only use categorizations to explain who we are as humans, we tend to start to view ourselves as objects. But we are not objects. “We become so absorbed and involved with things that we come to interpret ourselves as though we were just like things too. We are not things. We are no-thing” (Large, 2008). Heidegger describes humans as Being-in-the-world and differentiates us from objects due to our future-present temporality. It is our potential that makes us human. This separates us from objects that are ‘indifferent towards their potentialities’. An oak seed is only ever going to become a tree or it will not. A human can become a teacher, an astronaut, a drunk, etc.

We’ve just looked at the difference between humans and objects from a phenomenological lens. Let’s now look at one of the biggest creations in digital technology, the internet, and why this is important to my proposal stating that digital technology is expanding humans not just towards the objective reality, but elsewhere. Covid brought the performance arts to a halt, “performers and audience members have been separated and technology had to step in to give a lifeline to traditionally non-digital forms of art” (The Digital Human, 2020). In traditional theatres, the space between the seats and what happens on stage is where everyone in the room meets. Stanislavsky called this space a communion. But in new digital formats, where are the performers performing and where is the audience while watching? Where are the performers and audience meeting? What is the space we call the internet? While exploring where the internet might be I came across Journalistic Doc Searls who describes the internet as “Not a Thing, No thing” (Searls and Weinberger, 2015). This led me to use the same approach that Heidegger uses to describe Being, to analyse the internet.

Internet terms:

• Domain

• Site

• Address

• ‘Going on’ the internet

These terms are borrowed from our language to describe a place that exists in our objective world, creating a false sense that the internet is a tangible entity. We use the term to go ‘on’ the internet because we confuse the internet for a thing. But the internet is not a physical space, it does not have weight, and it’s not a place you can visit. This is summed up nicely when journalist Andrew Blume was told “There is a squirrel eating your internet” by a technician who came around to fix a problem he was having. But how could that be, “The internet is a transcendent idea, a set of protocols that has changed everything from shopping to dating, to revolutions. It was unequivocally not something a squirrel could chew on” (Blum, 2012).

Question – Could a squirrel chew on my Being?

So if the internet is not a thing or a place, then what or where is it? Marshall McLuhan described digital technologies as “extending our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time” (McLuhan, 1973). This statement was made before the invention of the internet and yet it couldn’t be more potent in describing what the world wide web is: an ”extension of our central nervous system”. There are further similarities between Heidegger’s ideas of Being and Doc Searls’s description of the internet. When Heidegger refers to human potentialities, he believes care to be the primary driving factor of movement. “That care is the Being of Dasien” (Large, 2008). Dasien refers to the experience of being that is peculiar to human beings. Why we strive to be something starts from our care towards it, and that care is what affords human potential. Doc Searls describes the “internet’s motive force as one of care” (Searls and Weinberger, 2015), realising that we are the medium online rather than the structures that make up the world wide web.

Digital As A Sight For Circus (Accessibility, Tensions & Space)

Accessibility.

I got into Circus at the age of twenty-four up until that point I was an Electrician, non-artist and traveller. I had not engaged with the performance arts in any way until I meet a Circus performer while in my early twenties. He inspired me to go and train and eventually go study Circus. Jump forward quite a few years and I finally end up here writing this literary review, and because of all this, now deeply connected with the performing arts. Due to my background, I would not have connected to any other form of performance art due to:

• The demand for prior knowledge.

• The lack of language needed to understand the performance as well as the terminology used in discussions and writings.

• The space which most performance arts inhabit.

• The lack of any connections or networks in the performing arts sector.

The Circus that I meet didn’t demand any of this from me. It allowed me in. The Circus tent transcends issues of social class, unlike the theatre space where social stratification can leave communities like the working class uncomfortable to enter. The travelling tent, not bound by brick and mortar, can reach further into communities. The form is accessible to any level of education compared to some higher forms of art, which can leave some audiences feeling alienated. The temporary space that is made in the tent is as raw and authentic as the performance. Contemporary Circus, for the most part, has let go of the traditional tent and has moved into the theatre. With the loss of the tent, Circus also experienced its biggest loss in reaching diverse audiences.

“We are digital beings now, and we are being made by digital technology and the Internet. No less human, but a lot more connected to each other” (Searls and Weinberger, 2015). The internet has brought the world closer. I can visit a museum in Stockholm, speak to a family member in the UK, play chess with a Mexican, and take a yoga class in Germany, all from a tiny digital screen that fits in my hand. The internet has made information that otherwise would have been kept for the few, now accessible to the masses. Lockdown has proven this ever more so with the performing arts. Established and recognised venues are now live-streaming performances to the world, and many, realising the reach, are aiming to continue post-Covid-19. The traditional tent and the internet both reach deeper into communities and engage more diverse audiences than a traditional theatre venue does. I would argue that finding a digital space for Circus would reignite the accessibility of Contemporary Circus that it has lost from its traditional past.

“Blast theory tends to use gaming and other interactive strategies in order to make its work more accessible and appealing to a wide demographic” (Broadhurst and Price, 2017).

Tensions

“Bodies and spaces are crucial to a live performance” (The Digital Human, 2020) and by placing Circus within a digital setting, both the space and the body are altered. Over this last year, as artists have taken to creating digital content during a time when live performance venues have been closed, we have seen this tension manifested in digital work. Through empirical research on placing Circus and live performances in digital spaces, I have pinpointed these tensions: the audience experience, the body, the trick, and the risk.

• The Audience Experience.

For a digital event, the audience experience is a lot different than a live one. What happens on stage is not the whole picture. Going out of your everyday space, the journey to the venue, and gathering are all part of the experience. Live performances can create a communion while in comparison digital spaces can isolate the audience, not only from the art but more importantly, isolate from each other.

• The Body.

Circus as an art form has traditionally been the celebration of the physical body. The virtuosic human tested and overcame our immediate environment: the head-balancer defying gravity, the trapeze artist flying through the air. Without the body, the traditional Circus would not exist. In the digital space, we can witness disembodied interactions, the human being replaced by avatars, profile pictures and tweets. Where does that leave Circus in the digital space, where we seem to lose the body in code?

• The Trick.

Circus makes anything possible. This is what I was told in my first two weeks of training at Circus training school. I believed it and I still do. Circus by pushing the limitations of the body gives the impression that it can do anything. Take the famous Cirque du Soleil. Stacks of humans standing on each other shoulders, an acrobat flipping and rotating across these human stacks as if physics doesn’t apply. But we all know this is a saying, physics does apply, and we as humans, Circus or not, are restricted by our reality. Well, in the digital realm, physics doesn’t apply. Unreal, a game engine used now not only by game companies but in most Hollywood films creates a space for a performer where anything is really possible. The digital realm exceeds the limitation given to us by this reality and therefore exceeds the possibilities Circus affords. We speak about Circus allowing anything to be possible, when really what it does is allow for the belief that anything is possible. Now with digital spaces, it’s not just a belief, but a reality, in a virtual sense. What happens to Circus, when in reality a double back somersault from the air is only possible through decades of dedication, but in a virtual space, flying is possible for anyone? In a space where anyone can do anything, where does Circus go? What does it become?

• The Risk.

One of the fundamentals of Circus is risk: “new Circus has sought innovative ways to challenge and confront audiences mediated by the human body. With a focus on emotive narrative representations of risk and death” (Game 2019). It comes back to Heidegger’s idea of human as potentialities. Risk puts the potentiality of human at the forefront of a Circus act. But what happens to the risk in Circus when it becomes digital? The Traditional Circus Sideshow acts to push the limits of what the human body is capable of. Whether it’s the virtuosic body, grotesque body, the painful body, all can have an audience in disbelief. In some circumstances, performers have to prove the realness of the act. The glass eater illuminating a bulb before breaking it. The sword swallower getting an audience member to check the authenticity of the sword. In the same way, a live-streamed performance must prove its liveness/realness. What is digital live? I will dive a little deeper into live streaming in the next chapter.

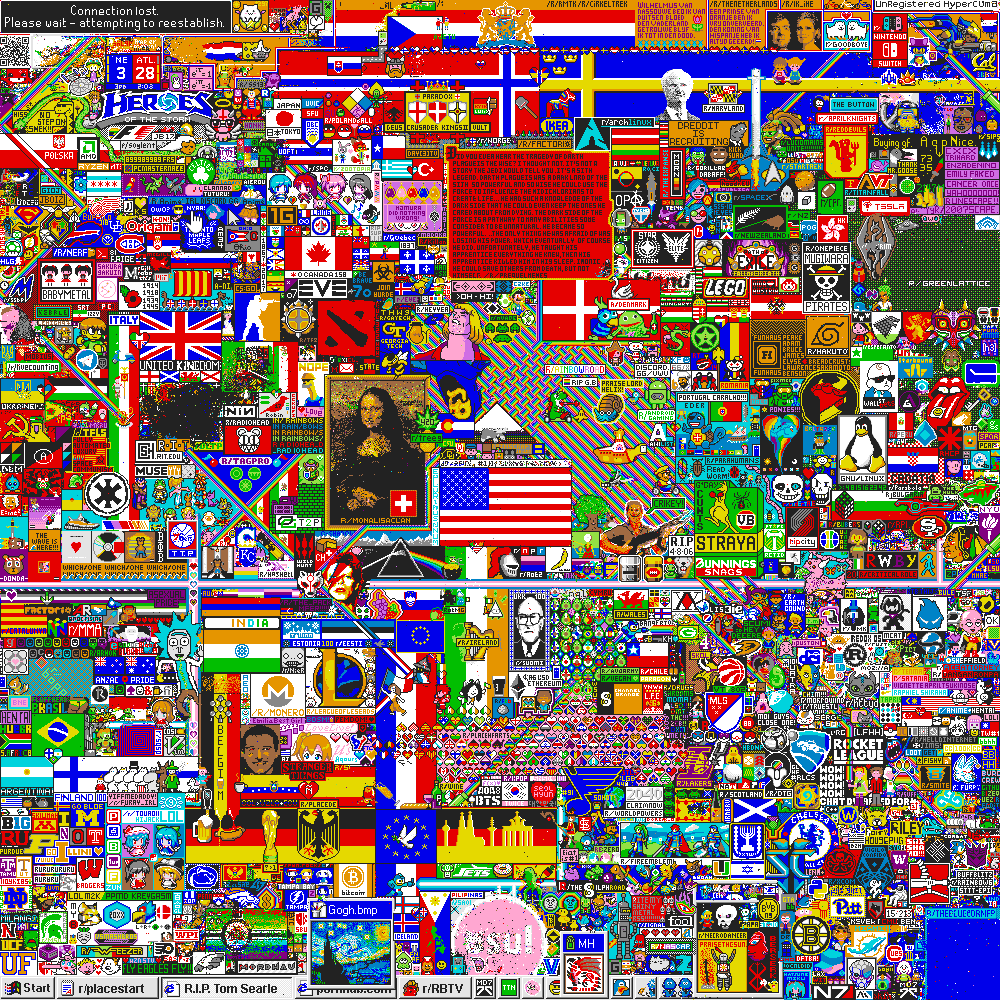

As we have all experienced, zoom is no match for a real-life meeting, the same as a live performance is no match for a live event which has been digitalised. But this is the problem. “When digital spaces try to recreate the offline experience” (The Digital Human, 2020) they miss the mark. We need to take away the pressure for digital experiences to offer real life. It cannot replicate real life, but it can enhance it. We need to use the digital space for what it can offer. Zoom has allowed us to meet from different parts of the world, something the real world cannot do. The camera allows for multiple perspectives and a closer look at the performers, whereas in a live setting we would only have one. We can manipulate time and space, we can alter our bodies, and we can give audiences a completely new experience, that the objective reality could never offer. The experiment called the Place “where Pixels collide” (THE ALTERNATIVE UK, 2017), shows we are able to create new ways to communicate and interact as we have never done before, which can “bring new meaning to the relationships with an audience” (The Digital Human, 2020).

Space (Live Streaming)

We’ve gone from digital to the internet, and now I want to zoom in even closer to a specific area of curiosity: live streaming. Live streaming is the transfer of online digital content to an audience in real-time. Even though Youtube created its first live streaming service in 2008, it didn’t become popular until Twitch started a service in 2011, and during the pandemic live streaming saw a 99% growth in hours watched. Humans have always favoured experiencing art and sport live, preferring a live concert to a music video. Live streaming has been proven to get up to 10x more engagement than pre-recorded videos, with people gravitating towards live broadcasts over traditional forms of content. Heidegger’s stance on potentialities can give us one answer to this phenomenon. “It is because Daisens (human Beings) are understood in terms of possibilities and not properties, that every existence is singular” (Large, 2008). A traditional pre-recorded video converts the potentialities into one objective experience rather than a human one. By being pre-recorded the possibility has already been established. Another answer to people’s engagement with live content is its instant interactivity. Digital live is an attempt to be in the space of the shared now, mediated by a virtual experience. These shared spaces are creating new ways to interact. CodeMiko is an example of a “streamer that reinvented themselves to create content that is unique and differentiated from the market”. (Anciuti and Stein, 2001). CodeMiko uses a motion capture suit, Unreal Engine, and creative coding to allow an audience to engage by physically changing her virtual environment and virtual body in real-time.

Digital As A Site For Circus

Is there a space for Circus in the digital Landscape? “Bluntly put, the new mixed reality paradigm foregrounds the constitutive or ontological role of the body in giving birth to the world” (Hansen, 2006). “Virtual reality serves to highlight the bodies function as, to quote phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, an ‘immediately given invariant’ a ‘primary access to the world’ the ‘vehicle of being in the world’. The body forms the absolute background, and absolute here, in relation to which all perceptual experience must be oriented. That is why virtual reality comprises something of a reality test for the body; as philosopher Alain Million points out, it ‘puts into place constraining apparatuses that allow us to better understand the limits and weakness (but also powers) of the body’” (Hansen, 2006). If Virtual reality and I would propose, all types of digital technology serve as a reality test for the body, then through this process, it will also test the understanding of Circus. I would argue against my previous statement ‘Without the body traditional Circus would not exist.’ and ask, can Circus exist without a body? This question can only be asked in digital spaces. With our current understanding of Circus and the body as being inseparable, when we say ‘Circus’, we also say ‘Body’. In VR the body as we know it ceases to exist, does this also mean that Circus ceases to exist or can it exist separately? By placing ourselves in these spaces, we will be able to pull apart what Circus is and what it is not. We can take this as a tangible example of McLuhan “We build the tools and then the tools build us”. We have built virtual reality which will feedback to us an understanding of our body and our world that we have yet to uncover.

Conclusion

Everyone is becoming aware of the problems facing our current technological climate. Pervasive computing, loss of privacy, and data collection are all major concerns around the world. The Digital era is paving the way for the future, and understanding what this space is / does / can do is a necessity to keep a grasp on our own existence. “Because the essence of technology is nothing technological, essential reflection upon technology and decisive confrontation with it must happen in a realm that is, on the one hand, akin to the essence of technology and, on the other, fundamentally different from it. Such a realm is art” (Hansen, 2006). Exploring spaces for Circus to exist in the digital landscape, will not only test and question the fundamentals of Circus but also question the foundations of our digital age. With Circus being an art form deeply connected to the body, it would be the perfect tool to shape our ongoing digital technogensis, and in doing so aim to make the digital environment more beautiful. Technology isn’t just something we use but becomes part of our makeup, just as “the cane is no longer an object for the ‘blind man’ but is part of his being” (REYNOLDS, 2017), so too is the mobile phone. Heidegger’s ‘Being’ and Doc Searls ‘Internet’ suggest that the web and us are the same, or at least exist in the same way. As McLuhan writes, the internet is just “an extension of our central nervous system”. The digital space cannot recreate our external world but is in itself world creating. As technology advances so to does the worlds that it creates, allowing more access to our bodily and sensory needs. “Interactive and digital media are supporting the multisensory mechanisms of the body and are thus, extending man’s space for play and action” (Hansen, 2006). “Technology springs from the very condition of human embodiment” (Broadhurst and Price, 2017) and with technological advancements connecting our full self in virtual spaces, as seen by creators like CodeMiko, digitalising humans is becoming ever more possible. Furthermore, digital technology has completely changed the way society, locally and globally interacts. “The technologies that change society are the ones that change social interactions” (Hidalgo, 2016). We’ve gone from sending lines of code, to sending bodily senses through the use of digital technology. The more we advance in technology, the more we can humanize it if “it is designed for and by the people who use it” (Koerner et al., 2020).

Reference list

Anciuti, G. and Stein, M. (2001). HOLOGRAPHIC INTERACTION: FROM DESIGN TO CONSTRUCTION

OF A HOLOGRAPHIC DISPLAY ANIMATED BY REAL-TIME MOTION CAPTURE. [online] . Available at:

https://www.ihci-conf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/05_202105L025_Anciuti.pdf [Accessed 6

Aug. 2021].

Atwood, M. (2013). Progress, Fear And Social Media”. Interview with Claire Sibonney. [online]Huffington Post. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/margaret-atwood-onprogre_n_4096727.

Blum, A. (2012). What is the Internet, really? [online] www.youtube.com. Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XE_FPEFpHt4&list=LL&index=29 [Accessed 6 Aug. 2021].

Broadhurst, S. and Price, S. (2017). Digital bodies : creativity and technology in the arts and

humanities. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bybyk, A. (2021). The Fascinating History of Live Streaming. [online] Ultimate Live Streaming Hub –

Restream Blog. Available at: https://restream.io/blog/history-of-live-streaming/.

Codemiko (n.d.). CodeMiko – Twitch. [online] www.twitch.tv. Available at:

https://www.twitch.tv/codemiko [Accessed 6 Aug. 2021].

Game, J. (2020). Music and Embodied Movement: Representations of Risk and Death in

Contemporary Circus”, Bennett, M.J. and Gracon, D. .

Hansen, M.B.N. (2006). Bodies in code : interfaces with digital media. New York ; London:

Routledge.

Hidalgo, C. (2016). How the medium shapes the message | Cesar Hidalgo |

TEDxYouth@BeaconStreet. [online] www.youtube.com. Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oy_hnx9TCJ8 [Accessed 6 Aug. 2021].

KoernerW., Asega, S., Dinkins, S., Earle, G., Haeyoung, A., Johnson, R., Kuo, R., Tsige Tafesse, Pioneer

Works Press, Creative Independent (Firm and Are.Na (Firm (2020). Software for artists book. #001:

Building better realities. Brooklyn: Pioneer Works Press.

Koetsier, J. (2019). Live Social Video Doubles Watch Time, Boosts Engagement 10X. [online] Forbes.

Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/12/30/live-social-video-doubleswatch-time-boosts-engagement-10x/?sh=9873eb93b8d7 [Accessed 7 Aug. 2021].

Large, W. (2008). Heidegger’s Being and time. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Mcluhan, M. (1973). Understanding media. London: Sphere Books.

Mcluhan, M. (2005). The medium is the message. Corte Madera Gingko Press.

REYNOLDS, J.M. (2017). MERLEAU-PONTY, WORLD-CREATING BLINDNESS, AND THE

PHENOMENOLOGY OF NON-NORMATE BODIES. [online] philarchive. Available at:

https://philarchive.org/archive/REYMWB.

Searls, D. (2021). What does the Internet make of us? [online] Medium. Available at:

https://dsearls.medium.com/what-does-the-internet-make-of-us-118421ac5e [Accessed 6 Aug.

2021].

Searls, D. and Weinberger, D. (2015). new Clues. [online] newclues.cluetrain.com. Available at:

https://newclues.cluetrain.com/ [Accessed 6 Aug. 2021].

THE ALTERNATIVE UK. (2017). When Pixels Collide: Reddit’s extraordinary collective art event.

[online] Available at: https://www.thealternative.org.uk/dailyalternative/whenpixelscollide

[Accessed 9 Aug. 2021].

The Builders Association (2014). 21st Century Storytelling with The Builders Association. [online]www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=R3RzoBVyZ0A&list=LL&index=46&t=3s [Accessed 6 Aug. 2021].

The Digital Human, (2020). BBC.

Wieser, M. (1991). Communications, Computing & Networks. Scientific America, 265(3).